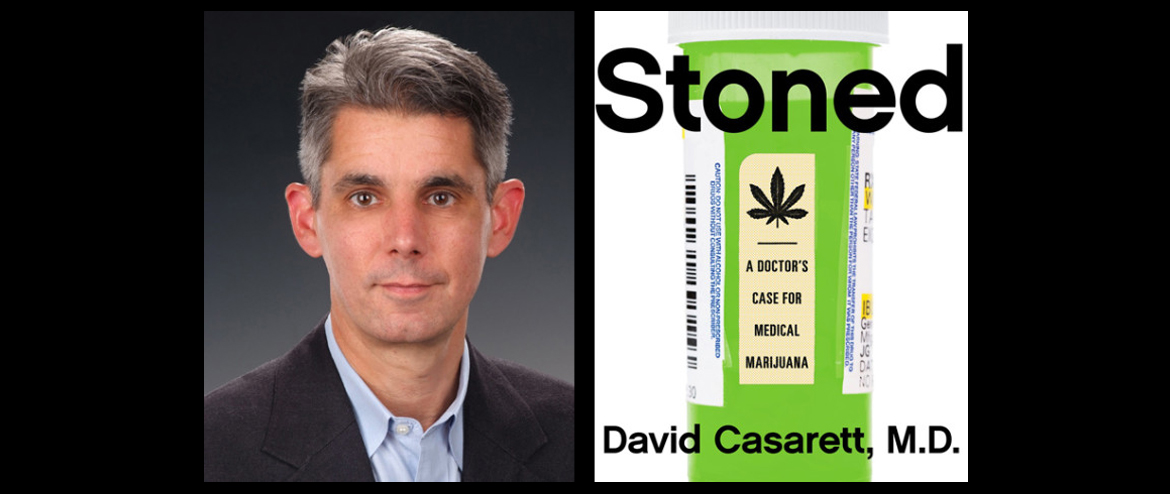

For his in-depth investigation of the science behind medical marijuana, University of Pennsylvania physician David Casarett sampled pot-infused wine, smeared marijuana paste on his legs, and took lessons in hash-making—and, of course, talked to a range of researchers and delved deep into the medical literature. We got a chance to talk with Casarett about what he learned and what changes, if any, his medical practice has made in the course of writing Stoned: A Doctor’s Case for Medical Marijuana.

(Note: this interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.)

World Science Festival: When you were in medical school, what did they teach you about marijuana, medical or otherwise?

David Casarett: Nobody in my medical school was talking about medical marijuana at all. The only place it showed up was as a drug of abuse, but it wasn’t discussed on the same terms as cocaine or heroin. Even from the perspective of risks it was kind of downplayed. My perception is that the medical profession has been really slow to think about the risks and benefits of medical marijuana. I actually heard about it mostly through the news.

One person who really got me thinking about this, though, was a patient who came to me for help with managing some of her pain symptoms. She asked me about medical marijuana, and I gave her the standard line: “It’s a drug of abuse, and it’s illegal, and there’s no evidence to support it.”

Now, this patient was a retired English professor who was used to being a pretty harsh taskmaster with her students, so she didn’t let me get away with that answer. She pushed me and said, “What do you mean there are no studies? I’ve found studies, haven’t you found studies?”

And I thought, well, actually, I don’t really know the different studies, because I’d never looked. So I promised her I’d look.

WSF: Do we know what it is that makes marijuana different from other pain relievers?

Casarett: We don’t have a great understanding of how it works. We’ve known about how non-steroidals like ibuprofen or aspirin work for centuries, and opioids almost as long—we know what those receptors are, we know what those receptors do. Marijuana is still a bit of a mystery.

We do know that if marijuana works for pain, it probably works best for what’s called neuropathic pain—pain not caused by a bruise or a broken bone, but caused by damage to the nerves themselves. This can happen after trauma, after an accident, or due to drugs or chemotherapy. A lot of people with chronic autoimmune diseases like lupus might have neuropathic pain, which is really hard to treat—it doesn’t respond well to non-steroidals or opioids. And yet there’s this growing evidence that it responds well to marijuana, but how that works is not really clear.

There’s some evidence that of the two main cannabinoids in marijuana—one is THC, which is the stuff that makes you feel stoned—a lot of the benefits of marijuana for pain, particularly neuropathic pain, come from cannabidiol or CBD, which doesn’t make you stoned.

WSF: What seems to be the best delivery mechanism for patients? Your chapter on pot-infused wine suggests that way doesn’t seem to work out so well …

Casarett: … Which is a shame, honestly. If pot-infused wine was medically useful, that would make the world a much better place.

But it’s actually not a question, much to my surprise, of what works better. There are delivery mechanisms like ointments that don’t seem to work as well, but the main forms used these days are either edibles or smoking or vaporizing. And what’s best depends on what you need and what you’re looking for.

The advantages of smoking or vaporizing are that you get those cannabinoids in your system really quickly. The edibles, on the other hand, give you a much longer tail of absorption and blood levels, so it takes a while. You lose a bunch through metabolism, you get a lower initial dose and a lower dose overall, but that dose will last for a while. So if you’re looking for a more long-term effect, then edibles work pretty well. The downside of edibles, though, is that the absorption will take a while, but it can be pretty hard to predict.

WSF: So are patients taking medical marijuana for the rest of their lives? Do they ever taper off?

Casarett: We really don’t know. And honestly, I think there’s so much we don’t know but could learn from patients who are taking medical marijuana: What are people using, how are they using it, what works, how does use change over time? We have a Kickstarter campaign going for a website, marijuanaresults.org, that’s designed to give people a community in which they could begin to share their experiences and through which we could see, as researchers, some of the answers to those questions.

WSF: It must be difficult for scientists to get research funding for these questions, given that marijuana’s still illegal at the federal level.

Casarett: My understanding is that the only way to get marijuana for research purposes is if you want to study it as a medication of abuse, which is not the goal of people who do this for a living, obviously. But I think it will probably get easier over time. There’s no way the federal government can look at medical marijuana legalization in 23 states plus the District of Columbia, hundreds of thousands of people using it … and then look at the database we have to work with. Something’s gotta give.

WSF: Are there any concerns we should have about side effects of marijuana?

Casarett: There certainly are, though some proponents of medical marijuana downplay those risks or ignore them entirely. The thing we should most be concerned about are the risks of getting high and driving—really not a good idea. I tell the story of what it’s like being in a car with someone behind the wheel who’s stoned. It’s not a pleasant experience, even in a carefully controlled parking lot situation.

Another big risk is addiction, which was a surprise to me. But the scientists who I talked to who study addiction think about marijuana addiction using the same brain circuitry they use to talk about addiction to alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, or heroin. They’ll say that the risk of addiction is lower for marijuana than for heroin or cocaine, but it’s still real. I don’t mean to be an alarmist, but it is a concern. If you’ve got, say, a one in 10 chance of becoming addicted to marijuana and you’re legalizing the stuff, and you have 10,000, 100,000, a million people using it, just simple math will indicate that pretty soon you’ll have a significant portion of the population addicted. That doesn’t neccessarily mean that the addiction will be strong enough to affect jobs and social relationships or destroy lives. But it is a concern we need to think about.

Personally, I say that when medical marijuana is legalized, there should be some requirement for counseling. When I prescribe an opioid for a patient, we talk about signs of addiction, the difference between addiction and tolerance. There really isn’t anything like that for medical marijuana and there should be.

WSF: Are you more likely to recommend medical marijuana to patients now?

Casarett: Pennsylvania does not have legal medical marijuana, so I can’t legally recommend it. It has changed my practice though. I’ve definitely gotten more assertive at responding to questions, because if people are using it, they need to know what the evidence is. If physicians aren’t talking about it in our conversations—whether we think it’s a good idea or not—then we’re doing our patients a disservice.

WSF: Are there any conditions where marijuana definitely doesn’t help?

Casarett: Certainly there are uses where the evidence hasn’t caught up yet. The things that really worry me are the proponents who claim that it works in the treatment of cancer. People really should not give up evidence-based chemotherapy and surgery for marijuana-based oils.

On the other hand, there is some evidence from cell culture studies that some of the components of marijuana may slow cell growth and slow the formation of new blood vessels, and may decrease tumor growth that way. Not near enough to say these marijuana-based oils treat cancer, but it’s possible that in 15 years or so, we’ll understand that science better and we’ll be able to use some form of cannabinoids that occur in marijuana as part of chemotherapy treatment.

There’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. Back in the ’30s and ’40s, people used to use cod liver oil to treat vitamin D deficiency in kids. They didn’t know what cod liver oil was or what it did, or what vitamin D was, but they knew that it worked. And that initial discovery led to a whole variety of studies that helped us understand what vitamin D is, where it comes from, what it does, and more broadly how the body metabolizes calcium and how it forms and destroys bone, and that led to a whole series of new drugs used for everything from cancer chemotherapy to osteoporosis.

We don’t use cod liver oil anymore, but it was a way of hacking into a complicated system. One thing to think about with medical marijuana is that maybe it’s kind of the cod liver oil of the 21st century. Maybe it’s a doorway into understanding the system of endocannabinoids that exist in all of us.

There are dozens of studies dating back to the 1950s that highlight the effect of marijuana and its related compounds on nausea. Not all of them are conclusive, but the weight of the evidence is pretty clearly on marijuana’s side. There’s also a synthetic cannabinoid called nabilone that was developed in the 1970s to treat nausea related to chemotherapy, and it worked very well.

How marijuana reduces nausea is a puzzle. The sensation of nausea is caused by the brain stem, the lower part of the brain that’s responsible for basic functions like breathing and throwing up. However, there don’t seem to be any cannabinoid receptors in the brain stem.

We know this because of a fascinating study in which researchers used twenty-two brains taken from three humans (who had died of non-neurologic disorders), twelve rats, four guinea pigs, two beagles, and one rhesus monkey. They sliced the brains paper thin, marinated those slices with a protein that binds to cannabinoid receptors, and linked that protein to a radioactive isotope. Then, they laid the slices of brain on a piece of radiation-sensitive film. Voila: a map of the brain’s cannabinoid receptors.

The main result was that although these cannabinoid receptors are widely distributed in the brain, they don’t seem to be located in the brain stem. If marijuana works to relieve nausea, it probably acts somewhere else—but where?

One possibility is the serotonin-based neural pathway in the gastrointestinal tract that involves the splenic nerve, which is one of the main nerve that controls digestion. The nausea caused by many chemotherapy agents seems to work through this pathway and, as we’ve seen, CBD binds to serotonin receptors. So, it’s possible that the CBD in marijuana works in the same way that other widely prescribed drugs such as ondansetron work.

A second “vestibular” pathway seems to operate through the labyrinth system in the ear. When that system senses motion that’s out of sync with what our eyes are seeing, we feel nauseated. If you’ve ever been car sick—or if you’ve had one too many martinis—you can thank that pathway. That pathway is different than the pathway by which chemotherapy drugs cause nausea, with different nerves, and different receptors. So we don’t know whether marijuana is useful in treating nausea associated with car sickness.

Finally, there’s an area of the brain that can make us feel nauseated. This area sits at the edge of the fourth ventricle, which is a sac that is filled with spinal fluid. It’s called the “chemotrigger zone” because it acts as the body’s poison control center. When it senses chemicals in spinal fluid that shouldn’t be in us, it prompts us to vomit. As solutions go, it’s not very elegant, but it’s effective. Here, too, we don’t know whether marijuana works on this pathway, but it’s possible.

Reprinted from Stoned: A Doctor’s Case for Medical Marijuana by David Casarett, M.D., with permission of Current, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright (c) David Casarett, 2015.

Image: Courtesy Shutterstock

Comments