From the rivers of the Amazon to the Lost Forest in Madagascar, evolutionary biologist Mark Siddall travels the world to discover the stunning diversity and behavior of leeches. Learn about his adventures and the important role leeches and other parasites play in our ecosystem. Includes a live demo of feeding leeches. Episode filmed live at the 2014 World Science Festival in New York City. The full Cool Jobs program from that year can be viewed online.Learn More

Mark Siddall:

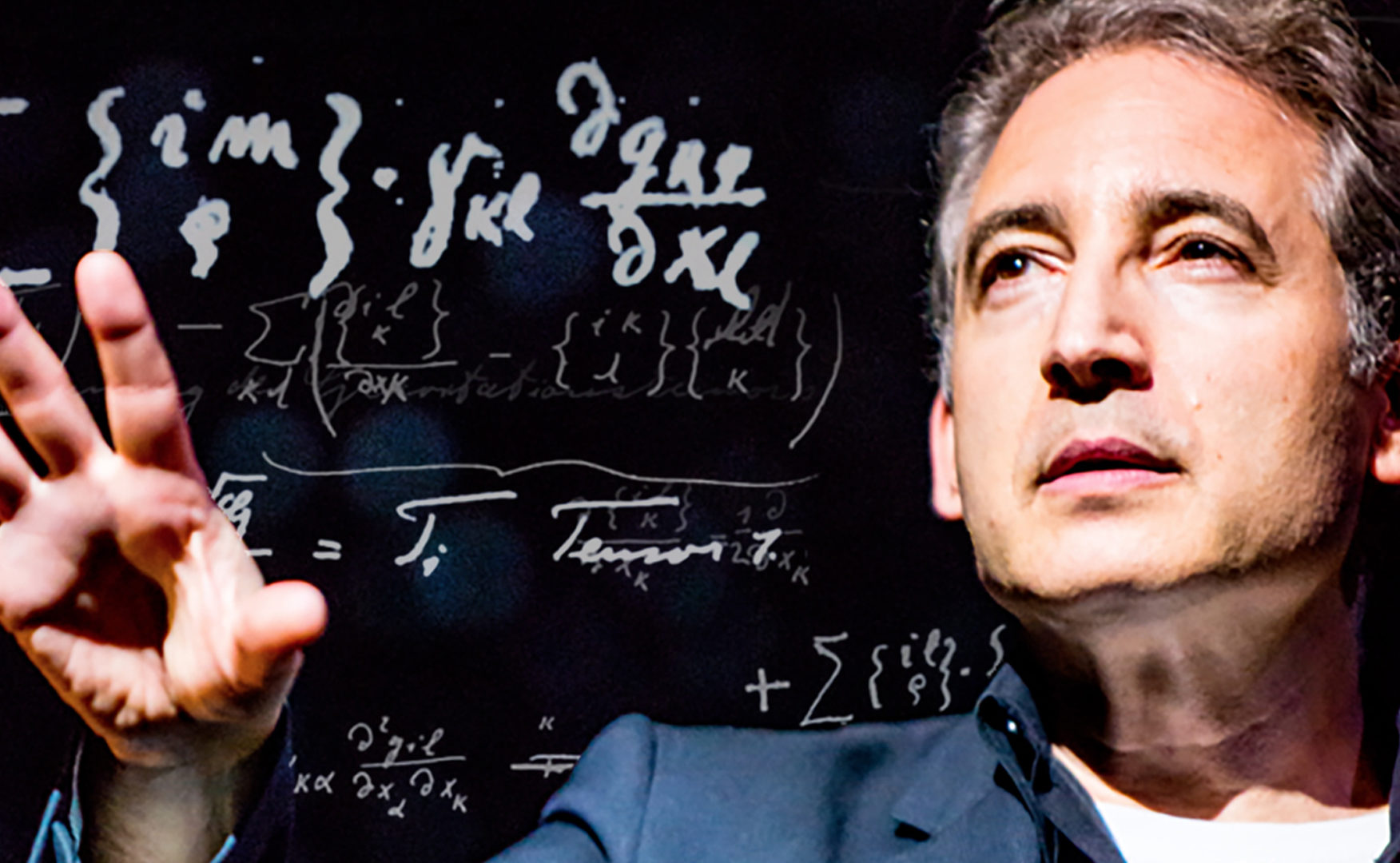

I have a pretty cool job. My name is Mark Siddall. I’m also known as the leech guy. I’m a curator at the American Museum of Natural History on the Upper West side of New York, where I work on leeches. And I work on a lot of other invertebrates, and I work on parasites. And you may wonder how I got to be the leech guy. It turns out that there is a word in almost every language for leech. And yet when I started doing this back in, say, the late 1980s, early 1990s, there were only about three people working on the biodiversity of leeches. When I get towards the end of my presentation, you’ll get a sense of how I sort of stumbled on becoming a leech expert.

Mark Siddall:

Most people think about leeches as being these black, slug-like worms that are lurking in dark waters and will come out and suck your blood. Well, if you look at those leeches really, really carefully in concentrate, you’ll actually see that they sometimes have very beautiful colors, like these orange polka dots going down the back of the North American Medicinal Leech. It also has a beautiful orange belly. And we study the diversity of leeches from around the world by looking at some of these color patterns, and looking at their internal anatomy. Now medicinal leeches, like the North American Medicinal Leech, Macrobdella decora, have three muscular jaws inside their mouth that have tiny little denticles, or teeth, with which they actually make an incision in your skin. From which they then feed on the upwelling blood. The circular sucker in the mouth, plus the teeth marks, leave you with a beautiful Mercedes-Benz mark, very prestigious. And it turns out we actually have some North American Medicinal Leeches with us.

Mark Siddall:

I’m going to draw a name from the audience at complete random. Is there a James Danziger out there somewhere? James? James, why don’t you come up here? Okay, James, these are North American Medicinal Leeches. Do you think you can get the lid off with me? Okay. Now just put that aside. Why don’t you have a seat in the chair? Can you roll up your left sleeve? You don’t want to do this? Okay. Well, why don’t you come over here then? And we’ll get Michael Tesler, my graduate student, to help out. Could you hold on to that? We might need that. Michael Tesler’s a graduate student at the Richard Gilder Graduate School, the American Museum of Natural History. Michael, are you ready?

Michael Tesler:

Oh, I’m ready. Yeah.

Mark Siddall:

Okay. James, could you take Michael’s arm and stick it in that jar of leeches? And don’t don’t let him take it out. Now, we’ll see how long that takes for those leeches to start feeding. It turns out leeches are actually beautiful animals. These are some Marine Leeches, some of these feed on Marine Turtles. Some of them feed on sharks. Some of them feed on other marine fishes. They’re really quite beautiful to behold. Other leeches, like the European Medicinal Leeches, we have Hirudo medicinalis on the left and a relative on the right, have beautiful color patterns. And some of the things that we’re looking at in terms of biodiversity and evolutionary biology also concerns how they manage to prevent blood from clotting, and how that’s evolved over time.

Mark Siddall:

And invariably, that involves proteins called anticoagulants in their saliva. Some of them prevent platelets from clotting. Others like Hirudin, which is one of the most potent antithrombin compounds, can keep you bleeding for up to 12 to 24 hours after a leech feeds. This little mess here is from the European Medicinal Leech. And James, if you would come over to this side and open this jar. Can you get it? There we go. And would you please hold his arm in there very forcefully. Don’t let him let go. Okay. That’s great. Michael, are you okay?

Michael Tesler:

So far so good.

Mark Siddall:

You don’t feel anything?

Michael Tesler:

No bites yet.

Mark Siddall:

Okay. Well hopefully we’ll get a good bite by the end. Let’s all give James a hand. Thank you, James.

Mark Siddall:

The European Medicinal Leeches were given to us courtesy of Leeches USA. Yes, there is a company out in Long Island called Leeches USA. Leeches are still used for medicinal purposes, mostly involved with reattachment of digits, and other things in terms of microsurgery.

Mark Siddall:

This is what we do in order to collect leeches in the wild. We go usually to a fairly remote place, where there’s water, and where we hope there are leeches. We roll our pant legs up. We take our shoes and socks off. Maybe wear sandals. Go wade into the water, up to knee level, or go wander into a jungle barefoot. Wiggle our legs around. The wiggling is actually really important because leeches can detect you from many, many meters away. They don’t need to be this close. Anything happening yet?

Michael Tesler:

Not quite yet.

Mark Siddall:

Okay. That’s the giant Amazonian Leech that is on my leg in French Guyana. Every once in a while, we take our legs out of the water to see if we have anything on. It requires a lot of balance. And then we pick them up, and look at them, and put them in jars. While we’re in the field, we spend a lot of time talking with the local people and trying to get them to understand what we’re doing. And the reaction is fairly universal. Yes. There are some dangers associated with wading around in water on various continents. I’ll just allude to some of them with pictures. Anyone want to go camping with me?

Speaker 3:

I do.

Mark Siddall:

I’m sorry. You may want to avert your gaze. Leeches do get into some strange places. I’ll change that. And we got notification from a colleague in Peru, that there were these children in the upper reaches of the Amazon that were all getting leeches up their noses, and it was very painful. And they sent us this leech, and it was a leech with the largest teeth ever. This is the ortho endoscope going up the nostril, and you’ll see the leech at the very end there, hanging onto this poor child’s mucus membranes. So I’m not going to get you with leech conservation, am I? Okay. Well, there was a leech with the largest teeth ever, and it was harming people in the Amazon. And so we gave it the name Tyrannobdella rex, so that we could say T-Rex is alive and well, feeding on children in the Amazon.

Michael Tesler:

The Hirudos just started feeding on me.

Mark Siddall:

The Hirudos just started feeding on him. Fantastic. Is it hanging on?

Michael Tesler:

I’ve got one on my hand, right there.

Mark Siddall:

Excellent.

Mark Siddall:

So Michael’s favorite leeches are the terrestrial leeches. Is there anybody from Australia out there, or from Southeast Asia, the Philippines? In those places, leeches are actually more often terrestrial than aquatic. And there’s a bunch of them up in here. They’re really, again, look how pretty those are. I mean, seriously.

Mark Siddall:

Now, there are some interesting things that you can do with terrestrial leeches. Some guys in Denmark went out to Vietnam, and they said, “We can’t actually go out and shoot all of these mammals that we want to figure out what …” By shoot. I mean, photographically. All of these mammals where they want to figure out what the diversity is, and what the habitat is like, and what their ranges are. And they came up with this great idea. Why not just collect all these terrestrial leeches on the ground, cut them open, take the blood meal out, and then DNA sequence the blood meal and find out which of the rare and endangered species are in the same place. Because that’s how the leeches would have got the blood.

Mark Siddall:

Well, so to give you a sense of how this all started, I actually grew up with a beautiful ravine across the road from the house that I grew up in. This is a very early picture of me in Canada. Thank you. This is a little later picture of me. And like a lot of the nine, 10, 11 year olds out there, I was really interested in science when I was young too. And this is actually … I did the science of maple syrup, that was my first science project for a science fair in class. When I got to high school and graduated high school, I thought, “Oh, I’m going to be a physician.” I was really interested in natural sciences and I wanted to be a medical doctor.

Mark Siddall:

When I went to college, on the other hand, I got the opportunity to do some blood parasite work with a professor at the University of Toronto, who was doing blood parasites of frogs and turtles and marine fishes. Now these are very much like malaria-like parasites, but of course, marine fishes don’t have a lot of mosquitoes biting them out in the wild. And it turned out that leeches were the things that were transmitting those parasites from one fish to another, from a turtle to a turtle. And I just accidentally became a leech expert, because I was studying all of these leeches to find the blood parasites that I was working on.

Mark Siddall:

Now, since then, I’ve done a lot of expeditions for the museum. This is just one in the Bolivian Andes. Prior to going to graduate school, this was the amount that I had traveled around the world. I had traveled across Canada, and I had been to England once. How are you doing? Feeling faint?

Michael Tesler:

I’m okay, yeah.

Mark Siddall:

Not feeling faint?

Michael Tesler:

No, these guys are pretty good biters on the right, yeah.

Mark Siddall:

Feel free to exclaim, “Ow.” But since then, this is how much of the world I’ve seen as a biodiversity expert. This is a really cool job, honestly. And all of that because I study leeches. And there’s only about 700 species or so.

Mark Siddall:

Now one of the things that I’m also known for, besides just studying leeches, is I have a great affection for food. It probably shows a little bit. Nova, in Nova Science Now, has this online program that they’ve done, you should go check out. It’s called The Secret Life of Scientists. And I was one of the very first ones to do this. You get to see all these scientists and what else do they do? And for me, it’s something that I call expeditionary gastronomy. Which means that wherever I go in the world, this is in Belem. Part of the Iquitos in Peru. I always go to the markets and find whatever crazy food … Well, this isn’t crazy food, that’s just normal food. Well, you’ll find strange fruits to eat. You’ll find strange animals to eat. This is in Incheon, China. There’s about five different phyla in that bucket. And it’s all there to be eaten. Some kind of mystery meat that I never figured out. These fish were actually really tasty. And instead of pigeons in the market, those are actually vultures running around on the ground, taking the place of pigeons.

Mark Siddall:

In Peru is where I first got the opportunity to eat beetle larvae. These guys are great. When they roast them up, they taste like popcorn with melted butter on them. The silkworms in Korea actually taste a little bit like sweet peas. Yeah, octopus sometimes sauces itself.

Mark Siddall:

So I’ve often been asked, because people know that I’ll eat just about anything if it’s put in front of me, have I ever eaten a leech? And the answer is yes. I roasted it over a fire. And so I can tell you that tastes a lot like charcoal. And the most common question that I get from people is, “How do you remove a leech?” And my answer is always the same. Let it finish. Thank you.

Mark Siddall:

How many?

Michael Tesler:

I got three.

Mark Siddall:

All right. Let’s get them off. Oh, dude. It’s kind of like getting chewing gum off your shoe on a hot summer day. Because they hold on with both ends. All right. How’d we do? Oh, geez, more?

Michael Tesler:

Not too much blood yet, but. It will come.

Mark Siddall:

There we go. Do you need this? Thanks, Michael.

From the rivers of the Amazon to the Lost Forest in Madagascar, evolutionary biologist Mark Siddall travels the world to discover the stunning diversity and behavior of leeches. Learn about his adventures and the important role leeches and other parasites play in our ecosystem. Includes a live demo of feeding leeches. Episode filmed live at the 2014 World Science Festival in New York City. The full Cool Jobs program from that year can be viewed online.Learn More

Mark Siddall is known as “the leech guy,” though he has focused on the evolutionary biology of a wide range of parasites. He has led expeditions around the world, most recently including South Sudan, Cambodia, and the Lower Amazon of Brazil.

Read More© 2008-2023 World Science Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

World Science Festival ® and its related logo are registered trademarks of the World Science Foundation. All Rights Reserved.